WW2: A Tribute to the RCAF-The Royal Canadian Air Force 1939-1945

An homage to all our brave ww2 Canadian war heroes past and present..."Courage is rightly esteemed the first of human qualities because it is the quality which guarantees all others" Winston Churchill. ***All the articles on this web page and pictures are a copyright of Lucky Luke***

Sunday, October 06, 2013

Ever wondered what was in a Red cross POW parcel in WW2?

The International Red cross aimed at distributing each POW with one Red Cross parcel each week. It might be Canadian, British, American, New Zealand or the equivalent in Argentine bulk. A few came from Brazil. In the early days some supplies came from Turkey. They consisted of stew, meat roll, Spam, vegetables, tea, coffee, cocoa, sugar, margarine, butter, biscuits, prunes, raisins, chocolate bars and soap; salt and Pepper, sweets, rolled oats, cheese, sometimes cigarettes. No one parcel could possibly contain all the items noted above. They varied between countries. For instance, Spam was in the Canadian parcel and not in the British. Vegetables were in the British and not in any others. New Zealand's had a very large tin of magnificent cheese, while the Canadian parcel had only small one. Canadian milk chocolate was at a premium as was New Zealand butter. The Scottish Red Cross parcels were the Only ones to contain rolled oats (and very good it was as an escaping ration, too)

Saturday, October 05, 2013

Picture taken in Toronto, July 1941

The four-engine Consolidated Liberator of the RCAF is a bomber to be manufactured on license in the Fort Worth plant of Canadian Car & Foundry Company. This type is being delivered to England from the San Diego plant and some are being used to fly ferry pilots back across the Atlantic. It is powered by four twin-row 1,200 h.p. Pratt & Whitney engines. Top speed is over 300 m.p.h and range is more than 3,000 miles

Monday, February 04, 2013

Spitfire base home to 24 RAF squadrons during WWII goes on the market for £1.5million after phone magnate decides to sell up

Spitfire base home to 24 RAF squadrons during WWII goes on the market for £1.5million after phone magnate decides to sell up

One of the best preserved Second World War airfields in the country has been put up for sale.

Perranporth, home of 24 RAF squadrons between 1941 and 1944, has been put on the market by former mobile phone magnate John George, with an asking price of £1.5million.

The 330-acre site in West Cornwall still features an original control tower, underground bunker, fighter shelters, pill boxes and the armaments depot which Mr George converted into the HQ of Jag Communications - once Britain's third largest independent mobile phones retailer.

Formed in 1989 in Cornwall, JAG Communications encompassed over 160 outlets in Cornwall, the South of England and Wales. At its height, over 600 people were employed across the UK.

As a result of the credit crunch, Jag was taken over by Go Mobile and Mr George quit the phones business. He has since set up an air taxi service in the Channel Islands.

An experienced pilot, Mr George bought the airfield four years ago to ease the commute from Guernsey where he is a tax exile.

He said: 'I bought Perranporth airfield because it was convenient'.

'I could land my plane and walk 100 yards from the end of the runway to be at my desk.

'When our shops went in 2010 we had to run down the head office and clearly I no longer needed an airfield.

'But I still love it. I've never thought of it as somewhere you own - more a place you look after until you pass it on.

'It just has an incredible atmosphere. You look out on a summer evening and think of all those crews who served here and you can't help but be affected by that.'

Perranporth was opened in April 1941 with a single runway and a large tent to serve as a barracks for the airmen. Officers were billeted in a local hotel.

The RAF planned at first to operate a single squadron of Spitfires to protect shipping and coastal towns from Luftwaffe raids.

But as the war moved on its role changed, and by 1942 two squadrons were based there, carrying out raids on northern France and escorting bombers in attacks on French ports.

The last Spitfires left in 1944 to be replaced by squadrons of Avengers and Swordfish tasked with hunting U and E Boats in the Atlantic.

Perranporth was never targeted by the Germans and according to English Heritage its 'defence landscape survives virtually as it was during World War II'.

The airfield is still fully operational and, despite competition from nearby Newquay Airport, has remained popular with both businessmen and holidaymakers visiting Cornwall.

Mr George, 51, says his estate agent, Savills, has already received more than 100 inquiries from potential buyers.

He said: 'It really is a fine example of our military heritage

'Whereas many RAF bases further east were bombed by the Germans, this one escaped damage.

'I want to see it thrive again and there's no doubt it can.'

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

The fourth tunnel called George

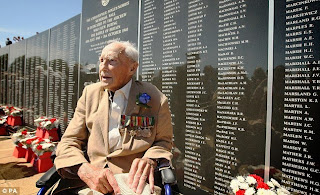

Frank Stone, seated, with Dr Tony Pollard on the site of George

This is an amazing story that i came across on the internet while surfing that i wanted to share with you. The true story of the great escape remains one of the great stories of the the Second World War. The men who tried to escape from Stalag Luft III at the price of their lives or that wanted to escape for that matter from any other World War two POW German prison camps were truly heroes.

It has lain hidden for nearly 70 years and looks, to the untrained eye, like a building site. But this insignificant tunnel opening in the soft sand of western Poland represents one of the greatest examples of British wartime heroism. And the sensational story became the Hollywood classic, The Great Escape, starring Steve McQueen.

Poignant memories: Frank Stone, left, and Gordie King with recovered artefacts including the pistol, below

We are standing in the notorious PoW camp Stalag Luft III, built at the height of the Third Reich, 100 miles east of Berlin. Ten thousand prisoners were kept under German guns here on a 60-acre site ringed with a double barbed-wire fence and watchtowers.

They slept in barrack huts raised off the ground so guards could spot potential tunnellers, but the Germans did not count on the audacity of British Spitfire pilot Squadron Leader Roger Bushell, played by Sir Richard Attenborough in the 1963 film. He was interned at the camp in March 1943. With him were about 2,000 other RAF officers, many of whom were seasoned escapers from other camps, with skills in tunnelling, forgery and manufacturing.

From them Bushell hand-picked a team for his ambitious plan: to dig their way out of captivity.

Three tunnels nicknamed Tom, Dick and Harry were constructed 30ft underground using homemade tools. While Tom was discovered and destroyed by the Germans, Dick was used for storage.

The third tunnel, Harry, became the stuff of folklore on the night of March 24, 1944, when Allied prisoners gathered in hut 104 before crawling along the 100ft tunnel to a brief taste of freedom. Only three escaped; 73 were rounded up by the Germans and 50 were summarily executed.

Few could have blamed their devastated comrades for sitting out the remainder of the war. Yet far from being dispirited, a few men began work on a fourth tunnel nicknamed ‘George’, which was kept so secret that only a handful of prisoners knew about it.

‘You have to admire these men,’ said chief archaeologist Dr Tony Pollard. ‘The Germans believed that the deaths of those 50 men would have acted as a deterrent for future escapees. But these men were even more determined.’

With us at the site are two of them: Gordie King, 91, an RAF pilot who operated the pump providing the tunnel with fresh air on the night of the Great Escape, and Frank Stone, 89, a gunner who shared a room with the ‘tunnel king’ Wally Floody, an ex-miner in charge of the digging. They stand, heads bowed, reminiscing about their former colleagues. It is the first time Gordie, who was shot down on his first mission to Bremen in 1942, has returned to the camp since he and the remaining prisoners of war were marched out on January 27, 1945, as Russian forces approached.

‘It has been very emotional,’ he said. ‘It brings back such bittersweet memories. I am amazed by everything they have found.’

A widower with six children, he has vivid memories of working on tunnel Harry, performing guard duty and acting as a ‘penguin’ to disperse the sand excavated from the tunnels, whose entrances were hidden by the huts’ stoves.

They were called penguins because they waddled when they walked.

‘We would put bags around our neck and down our trousers, fill them with excavated sand, then pull a string to release it on to the field where we played soccer, all in a very nonchalant way,’ Gordie said.

‘One of my jobs was to look out of the window at the main gate 24 hours a day and write down how many guards went in and out,’ he recalled. ‘Another was warning watch. If the Germans came into the compound, we would pull the laundry line down and everyone would stop what they were doing and resume normal duties. The guards were not exactly brilliant. They were taken from what we called 4F – not fit for frontline fighting.

I’m thrilled by it all,’ added Frank, who was shot down on his second mission: a bombing raid on Ludwigshafen oil refinery. ‘It’s like a war memorial for me. I don’t want people ever to forget the 50 men who died. The escape was thrilling and exciting but those men paid the price for it.’

Inevitably security tightened after the Great Escape and an inventory was taken by the Germans to gauge the extent of the operation. The roll- call of hidden items is astounding: 4,000 bedboards, 90 double bunk beds, 635 mattresses, 62 tables, 34 chairs, 76 benches, 3,424 towels, 2,000 knives and forks, 1,400 cans of Klim powdered milk, 300 metres of electric wire and 180 metres of rope.

To prevent further escape attempts, the Germans filled in Harry with sand. So effective was the cover-up that when the remaining prisoners wanted to build a memorial for the 50 men who died, the exact site of the tunnel could not be agreed on.

Now, for the first time in 66 years, the archaeologists have pinpointed the entrance shaft to Harry after compiling a map of the camp using aerial photography.

What was most surprising for the team was the structure within the shaft. The bedboards were interlocked to line the tunnel but the sand was so soft that plaster and sandbags were used to prevent it engulfing the tunnel. Amazingly, the ventilation shaft, which was made out of discarded powdered milk tins, was still intact.

Dr Pollard, 46, who co-founded Glasgow University’s Centre for Battlefield Archaeology, said: ‘I was surprised at just how emotional I became when we found Harry. We were the first people to see the tunnel in decades. But it came to a point when we realised we couldn’t progress with the excavation. As soon as you drive a shaft into the sand, it is so soft it starts to collapse. It shows just how skilled those prisoners were.’

After abandoning Harry, the team set their sights on finding the secret fourth tunnel rumoured to have been dug underneath the floorboards in the camp theatre.

Using ground-scanning radar equipment, they found – beneath what would have been seat 13 – the trap door to a space that gave real insight into how the earlier tunnels would have been built.

To the left, between the floor joists, was a storage area for equipment – Klim tins, tools, a trolley and the ventilation pump – and abandoned sand. A few feet away was the entrance to the tunnel shaft, and at its bottom a separate chamber, which archaeologists believe was the radio room.

Down a single step lay the tunnel itself, intricately shored with bed boards, wired for light and equipped with the trademark trolley system used to shift both sand and men quickly and silently through the tunnels. It looked like a miniature railway with trolleys running on tracks linked by rope and pulled along by men at either end.

‘George turned out to be an absolute gem,’ explained Dr Pollard. ‘We found the shaft and excavated the tunnel which ran the entire length of the theatre. It was incredibly well preserved, with timber-lined walls, electrical wiring and homemade junction boxes, and was tall enough to walk through at a stoop. The craftsmanship is phenomenal. You can even see the groove on the top of the manhole cover, where it would swivel and slot into the floorboard above.

‘It was built at a time of heightened security at the camp. It is a fighting tunnel, not an escape tunnel. It was heading for the German compound from where the prisoners hoped to steal weapons and fight their way out.

The men knew the end of the war was nigh and they were playing a dangerous game. To see what most of the prisoners never saw was a real thrill. The Germans obviously discovered Harry but they never had a clue about George.’

The massive collection of artefacts found inside the tunnel included trenching tools; a fat-burning lamp crafted from a Klim tin; solder made from the silver foil of cigarette packets for the wiring system; a belt buckle and briefcase handle from the escapers’ fake uniforms as well as a German gun near hut 104. They also uncovered the axle and wheels from one of the tunnel trolleys, identical to the one used in Harry, and the remains of an air pump; a kind of hand-operated bellows which drew fresh air from the surface down a duct to the tunnel.

But the piece de resistance was a clandestine PoW radio crafted from a biscuit box and cannibalised from two radios smuggled into the camp.

Tunnel vision: A tunnel reconstruction showing the trolley system, tried out by Frank, 89

Frank was instrumental in making the coil for the radio, which he moulded from an old 78 record. ‘I helped with the work on the construction of the radio, doing the soldering and things like that,’ he recalled, ‘cutting out bits of tins and whatever we needed for the equipment.’

Gordie added: ‘I remember one day walking around the camp with a friend when we saw this huge coil of wire. We grabbed it, covered it up with our coats and took it back to the hut. The Germans could not understand where the wire went. Until then we had had to rely on old tins of margarine with a wick in them, made from pyjama cord, to light the tunnel, but they were smoky, used up oxygen and were continually getting knocked out.’

On the night of the Great Escape, 200 prisoners, allocated consecutive numbers, gathered in hut 104 to make their escape, each a few minutes apart. The leaders were dressed in German uniforms or specially tailored civvies and kitted out with maps, compasses and forged documents.

Gordie, who was slot 140, remembers sharing final words with many of the escapers, wishing them luck and complimenting them on ‘their impressive disguises’.

‘It was quite exciting,’ he said. ‘Only the key German-speaking officers, who had a good chance of bluffing their way through, were given documents and civilian uniforms. The rest of us were so-called hard-a**ers, who were expected to get out and run.’

War classic: Steve McQueen on the set of the classic movie, The Great Escape

According to Roger Bushell’s plan, thousands of German soldiers and police would be deployed to hunt the escapers, preventing them from fighting the Allies. But after 76 men had escaped, the remainder were caught leaving the tunnel by German guards. Seventy-three of the men who got away were rounded up over the next few weeks and 23 were returned to the camp. The other 50 were shot in the back of the head by the guards at the side of the road. Only three escapees, Norwegians Per Bergsland and Jens Muller, and Dutch fighter pilot Bram van der Stok, succeeded in reaching safety. Bergsland and Muller got to neutral Sweden and Van der Stok made it to Gibraltar via Holland and France.

‘Afterwards the morale in the camp was very depressed,’ said Frank, tears in his eyes. ‘It was eerie. We had a period of mourning and held a memorial service. People just wandered around the camp quietly.’

‘A mass of doom enveloped the whole camp as so many of us had friends who were shot,’ added Gordie. ‘My close friend Jimmy Wernham, who came from the same town as me, was one of those who didn’t come back.

‘Before he went out, he took his ring off and gave it to his roommate Hap Geddes, who wasn’t going out, and said, “If anything happens to me, I want you to take this ring and give it to my fiancee.” After the war, Hap took the ring back to Dorothy and struck up a relationship with her. He ended up marrying her. He is still alive and living in Canada.’

Frank added: ‘I hope that what has been revealed will remind everybody what we went through and how we met the challenges. It was a privilege to be involved.’

This is an amazing story that i came across on the internet while surfing that i wanted to share with you. The true story of the great escape remains one of the great stories of the the Second World War. The men who tried to escape from Stalag Luft III at the price of their lives or that wanted to escape for that matter from any other World War two POW German prison camps were truly heroes.

It has lain hidden for nearly 70 years and looks, to the untrained eye, like a building site. But this insignificant tunnel opening in the soft sand of western Poland represents one of the greatest examples of British wartime heroism. And the sensational story became the Hollywood classic, The Great Escape, starring Steve McQueen.

Poignant memories: Frank Stone, left, and Gordie King with recovered artefacts including the pistol, below

We are standing in the notorious PoW camp Stalag Luft III, built at the height of the Third Reich, 100 miles east of Berlin. Ten thousand prisoners were kept under German guns here on a 60-acre site ringed with a double barbed-wire fence and watchtowers.

They slept in barrack huts raised off the ground so guards could spot potential tunnellers, but the Germans did not count on the audacity of British Spitfire pilot Squadron Leader Roger Bushell, played by Sir Richard Attenborough in the 1963 film. He was interned at the camp in March 1943. With him were about 2,000 other RAF officers, many of whom were seasoned escapers from other camps, with skills in tunnelling, forgery and manufacturing.

From them Bushell hand-picked a team for his ambitious plan: to dig their way out of captivity.

Three tunnels nicknamed Tom, Dick and Harry were constructed 30ft underground using homemade tools. While Tom was discovered and destroyed by the Germans, Dick was used for storage.

The third tunnel, Harry, became the stuff of folklore on the night of March 24, 1944, when Allied prisoners gathered in hut 104 before crawling along the 100ft tunnel to a brief taste of freedom. Only three escaped; 73 were rounded up by the Germans and 50 were summarily executed.

Few could have blamed their devastated comrades for sitting out the remainder of the war. Yet far from being dispirited, a few men began work on a fourth tunnel nicknamed ‘George’, which was kept so secret that only a handful of prisoners knew about it.

Now, for the first time in 66 years, the archaeologists have pinpointed the entrance shaft to Harry after compiling a map of the camp using aerial photography.

‘You have to admire these men,’ said chief archaeologist Dr Tony Pollard. ‘The Germans believed that the deaths of those 50 men would have acted as a deterrent for future escapees. But these men were even more determined.’

With us at the site are two of them: Gordie King, 91, an RAF pilot who operated the pump providing the tunnel with fresh air on the night of the Great Escape, and Frank Stone, 89, a gunner who shared a room with the ‘tunnel king’ Wally Floody, an ex-miner in charge of the digging. They stand, heads bowed, reminiscing about their former colleagues. It is the first time Gordie, who was shot down on his first mission to Bremen in 1942, has returned to the camp since he and the remaining prisoners of war were marched out on January 27, 1945, as Russian forces approached.

‘It has been very emotional,’ he said. ‘It brings back such bittersweet memories. I am amazed by everything they have found.’

A widower with six children, he has vivid memories of working on tunnel Harry, performing guard duty and acting as a ‘penguin’ to disperse the sand excavated from the tunnels, whose entrances were hidden by the huts’ stoves.

They were called penguins because they waddled when they walked.

‘We would put bags around our neck and down our trousers, fill them with excavated sand, then pull a string to release it on to the field where we played soccer, all in a very nonchalant way,’ Gordie said.

‘One of my jobs was to look out of the window at the main gate 24 hours a day and write down how many guards went in and out,’ he recalled. ‘Another was warning watch. If the Germans came into the compound, we would pull the laundry line down and everyone would stop what they were doing and resume normal duties. The guards were not exactly brilliant. They were taken from what we called 4F – not fit for frontline fighting.

I’m thrilled by it all,’ added Frank, who was shot down on his second mission: a bombing raid on Ludwigshafen oil refinery. ‘It’s like a war memorial for me. I don’t want people ever to forget the 50 men who died. The escape was thrilling and exciting but those men paid the price for it.’

Inevitably security tightened after the Great Escape and an inventory was taken by the Germans to gauge the extent of the operation. The roll- call of hidden items is astounding: 4,000 bedboards, 90 double bunk beds, 635 mattresses, 62 tables, 34 chairs, 76 benches, 3,424 towels, 2,000 knives and forks, 1,400 cans of Klim powdered milk, 300 metres of electric wire and 180 metres of rope.

To prevent further escape attempts, the Germans filled in Harry with sand. So effective was the cover-up that when the remaining prisoners wanted to build a memorial for the 50 men who died, the exact site of the tunnel could not be agreed on.

Now, for the first time in 66 years, the archaeologists have pinpointed the entrance shaft to Harry after compiling a map of the camp using aerial photography.

What was most surprising for the team was the structure within the shaft. The bedboards were interlocked to line the tunnel but the sand was so soft that plaster and sandbags were used to prevent it engulfing the tunnel. Amazingly, the ventilation shaft, which was made out of discarded powdered milk tins, was still intact.

Dr Pollard, 46, who co-founded Glasgow University’s Centre for Battlefield Archaeology, said: ‘I was surprised at just how emotional I became when we found Harry. We were the first people to see the tunnel in decades. But it came to a point when we realised we couldn’t progress with the excavation. As soon as you drive a shaft into the sand, it is so soft it starts to collapse. It shows just how skilled those prisoners were.’

After abandoning Harry, the team set their sights on finding the secret fourth tunnel rumoured to have been dug underneath the floorboards in the camp theatre.

Using ground-scanning radar equipment, they found – beneath what would have been seat 13 – the trap door to a space that gave real insight into how the earlier tunnels would have been built.

To the left, between the floor joists, was a storage area for equipment – Klim tins, tools, a trolley and the ventilation pump – and abandoned sand. A few feet away was the entrance to the tunnel shaft, and at its bottom a separate chamber, which archaeologists believe was the radio room.

After abandoning Harry, the team set their sights on finding the secret fourth tunnel rumoured to have been dug underneath the floorboards in the camp theatre.

Down a single step lay the tunnel itself, intricately shored with bed boards, wired for light and equipped with the trademark trolley system used to shift both sand and men quickly and silently through the tunnels. It looked like a miniature railway with trolleys running on tracks linked by rope and pulled along by men at either end.

‘George turned out to be an absolute gem,’ explained Dr Pollard. ‘We found the shaft and excavated the tunnel which ran the entire length of the theatre. It was incredibly well preserved, with timber-lined walls, electrical wiring and homemade junction boxes, and was tall enough to walk through at a stoop. The craftsmanship is phenomenal. You can even see the groove on the top of the manhole cover, where it would swivel and slot into the floorboard above.

‘It was built at a time of heightened security at the camp. It is a fighting tunnel, not an escape tunnel. It was heading for the German compound from where the prisoners hoped to steal weapons and fight their way out.

The men knew the end of the war was nigh and they were playing a dangerous game. To see what most of the prisoners never saw was a real thrill. The Germans obviously discovered Harry but they never had a clue about George.’

The massive collection of artefacts found inside the tunnel included trenching tools; a fat-burning lamp crafted from a Klim tin; solder made from the silver foil of cigarette packets for the wiring system; a belt buckle and briefcase handle from the escapers’ fake uniforms as well as a German gun near hut 104. They also uncovered the axle and wheels from one of the tunnel trolleys, identical to the one used in Harry, and the remains of an air pump; a kind of hand-operated bellows which drew fresh air from the surface down a duct to the tunnel.

But the piece de resistance was a clandestine PoW radio crafted from a biscuit box and cannibalised from two radios smuggled into the camp.

Tunnel vision: A tunnel reconstruction showing the trolley system, tried out by Frank, 89

Frank was instrumental in making the coil for the radio, which he moulded from an old 78 record. ‘I helped with the work on the construction of the radio, doing the soldering and things like that,’ he recalled, ‘cutting out bits of tins and whatever we needed for the equipment.’

Gordie added: ‘I remember one day walking around the camp with a friend when we saw this huge coil of wire. We grabbed it, covered it up with our coats and took it back to the hut. The Germans could not understand where the wire went. Until then we had had to rely on old tins of margarine with a wick in them, made from pyjama cord, to light the tunnel, but they were smoky, used up oxygen and were continually getting knocked out.’

On the night of the Great Escape, 200 prisoners, allocated consecutive numbers, gathered in hut 104 to make their escape, each a few minutes apart. The leaders were dressed in German uniforms or specially tailored civvies and kitted out with maps, compasses and forged documents.

Gordie, who was slot 140, remembers sharing final words with many of the escapers, wishing them luck and complimenting them on ‘their impressive disguises’.

‘It was quite exciting,’ he said. ‘Only the key German-speaking officers, who had a good chance of bluffing their way through, were given documents and civilian uniforms. The rest of us were so-called hard-a**ers, who were expected to get out and run.’

War classic: Steve McQueen on the set of the classic movie, The Great Escape

According to Roger Bushell’s plan, thousands of German soldiers and police would be deployed to hunt the escapers, preventing them from fighting the Allies. But after 76 men had escaped, the remainder were caught leaving the tunnel by German guards. Seventy-three of the men who got away were rounded up over the next few weeks and 23 were returned to the camp. The other 50 were shot in the back of the head by the guards at the side of the road. Only three escapees, Norwegians Per Bergsland and Jens Muller, and Dutch fighter pilot Bram van der Stok, succeeded in reaching safety. Bergsland and Muller got to neutral Sweden and Van der Stok made it to Gibraltar via Holland and France.

‘Afterwards the morale in the camp was very depressed,’ said Frank, tears in his eyes. ‘It was eerie. We had a period of mourning and held a memorial service. People just wandered around the camp quietly.’

‘A mass of doom enveloped the whole camp as so many of us had friends who were shot,’ added Gordie. ‘My close friend Jimmy Wernham, who came from the same town as me, was one of those who didn’t come back.

‘Before he went out, he took his ring off and gave it to his roommate Hap Geddes, who wasn’t going out, and said, “If anything happens to me, I want you to take this ring and give it to my fiancee.” After the war, Hap took the ring back to Dorothy and struck up a relationship with her. He ended up marrying her. He is still alive and living in Canada.’

Frank added: ‘I hope that what has been revealed will remind everybody what we went through and how we met the challenges. It was a privilege to be involved.’

Sunday, November 20, 2011

The train jumpers

This is an exciting sketch of the means of escape quite frequently practiced by Allied prisoners of War while being transferred between prisonner of war camps. The following picture from a train is both graphic and realistic. The jump involves spirit, perfect timing and steady nerves. The German guards must be caught off balance. They may be at the other end of the corridor or perhaps just looking the other way. There may be planned diversion - the guards attention has been diverted either by a German speaker or a commotion in some other part of the carriage. At the given moment the prisoner makes his jump. A comrade chucks his equipement out after him. It will contain some spare clothing, a bit of food, perhaps a map, most likely a home made compass.

What the Allied prisonners of war had to endure while escaping the German Army must have been quite frightening. An allied prisonner escaping knew that if caught by the German army, he would be handed over to the Gestapo for questionning. This soldier, airman or sailor knew that his life would be in the hands of the Gestapo interrogator. He was either subject to torture or hours on end of questionning or both without very little food or water. Very often, if the prisonner survived the intterogation, he would be sent to Colditz castle. No allied prisonner of war wanted to be sent to Colditz, the old castle on a mountain top near Leipzig, Germany, it was cold, damp and practically with no means of escape.

The only thing an Allied prisonner of war wanted to do is escape to the nearest country either to Spain or Switzerland where the Nazi regime was not in place or very neutral and to be able to contact the resistance and be helped back home to England to fight again against the Nazi regime and bring it to it's knees so the Allies could all end the war and return to a normal life once again but escaping from Colditz was probably as hard to escape as to trying to stay alive during the war on a major battlefield. Life at Colditz was miserable for any Allied prisonner of war.

Friday, November 11, 2011

In Flanders Fields / Poème au champ d'honneur

In Flanders Fields

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead.

Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved, and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders Fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders Fields.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Poème au champ d'honneur

Au champ d'honneur, les coquelicots

Sont parsemés de lot en lot

Auprès des croix; et dans l'espace

Les alouettes devenues lasses

Mêlent leurs chants au sifflement

Des obusiers.

Nous sommes morts,

Nous qui songions la veille encor'

À nos parents, à nos amis,

C'est nous qui reposons ici,

Au champ d'honneur.

À vous jeunes désabusés,

À vous de porter l'oriflamme

Et de garder au fond de l'âme

Le goût de vivre en liberté.

Acceptez le défi, sinon

Les coquelicots se faneront

Au champ d'honneur.

Monday, November 15, 2010

Larry Carter, RCAF Pilot, KIA

This amazing story was sent to me by someone that wished to remain anonymous. The link to this story was sent through my tribute to the RCAF email address. I thought that this story of courage, should be posted on my blog. This young man's name is Larry Carter as seen on the Flickr link which can be viewed simply by double clicking on the title, Larry Carter, RCAF Pilot, KIA, above. I would have liked to respond to the person who has sent me this link, to know, if i can make a copy of the Flickr page and post it my my blog? Who ever is the rightful owner of the picture and story, if you have any objections or comments, please let me know! In the mean time, i though that it would be beautiful to post this story of courage and sacrifice by a another truly brave Canadian by the way who trained at the RCAF base in Lachine in which, i have made a previous article on my blog. Thank you Larry for your courage.

Larry was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, on January 23, 1924. His father was Roy Cuthbert Carter, and his mother was Josephine Stovel. He was one of the best educated of the crew, having achieved his senior matriculation (grade 12). He enjoyed hockey, football and track. Larry enlisted at Windsor, Ontario, on May 20, 1942. His first station was at #5 Manning Depot in Lachine, Quebec, where he learned military discipline, aviation basics, regulations, history, and navigation. Between courses he engaged in endless drills and weapon-handling exercises.

At #3 Initial Training School, Victoriaville, Quebec, it was found that Larry had the aptitude to be a bomber pilot. He was tested on a LINK flight simulator, which was a grueling test of one’s capabilities.

While attending #11 Elementary Flying Training School at Cap de la Madelaine, Quebec, Larry flew De Havilland Moth and Fairey Fleet training aircraft.

At #5 Special Service Flying School in Brantford, Ontario, Larry trained in Avro Ansons (known as the ‘greenhouse’ because of its wrap-around cockpit).

Larry was awarded his pilot’s badge on January 10, 1943. On October 22, 1943, he embarked from Halifax, and disembarked in Britain on October 30, 1943.

Upon arriving in Britain, he was first stationed at No. 3 Personnel Reception Centre in Bournemouth, Dorset, while waiting for openings to become available at advanced training units.

I’m a little bit sketchy concerning his precise training at 26 Elementary Flying Training School at Theale in Berkshire, RAF Gaydon in Warwickshire, 14 (P) AFU at Ossington in Nottinghamshire and Dallachy, Moray, Scotland.

At 83OTU Peplow, he trained on Wellington bombers, and it was here he was killed on a night training mission, July 22/23, 1944.

The commanding officer at Victoriaville found him to be “… a bright-eyed youngster with excellent Service Spirit. [He is ] very anxious to make good as any part of aircrew. Working very hard. [He] is keen, well-disciplined and should do well as captain of an aircraft”

Larry’s body was recovered from the sea east of Afonwen Junction, Caernarvonshire, on August 4, 1944, and he was buried at Blacon cemetery in Chester, on August 4, 1944

Sunday, September 05, 2010

The many behind the few: TV's David Jason takes to the skies in a Second World War Spitfire to pay tribute to the Battle of Britain's heroes...

During the Battle of Britain, those fighter pilots lucky enough to have dodged the Luftwaffe’s deadly bullets always performed a ritual on their way home.

They would wait until they were flying just above the White Cliffs of Dover – the very symbol of everything they were fighting for – and flip their Spitfire or Hurricane in an exuberant barrel-roll of honour.It was a kind of ecstatic, airborne dance of victory. Recently, while filming my forthcoming ITV documentary on the Battle of Britain, I got to experience just a little of what they must have felt.

Not only did I get to fly a Spitfire – with the help of a trusting trainer, Carolyn Grace, in the front – but I also got to experience the stomach-tumbling joy of the ritual myself.

That day I had already soared high above the English Channel in a plane steeped in military history.

My Spitfire had flown 300 combat hours during the Second World War and had shot down the first enemy plane during D-Day. It had been mind-blowing to imagine the steel required by pilots to keep their nerve, their course steady and their aim true while bullets flew past them in all directions. But the best was yet to come. As we flew back, Carolyn said: ‘Just imagine, you’re returning home after surviving your latest battle with the Luftwaffe. Now look over there.’ And as I did, I saw the White Cliffs looming majestically up from the sea.

‘Shall we do the barrel-roll?’ she asked. The answer had to be ‘yes’. Carolyn took the controls and we flipped in a glorious double somersault, careening above the cliffs with the magnificence of an eagle.

There are not too many things in life that have reduced me to tears but this was one of them. I felt humbled and so proud of those men who fought for us in our darkest hour. It’s an experience that will never leave me.

For me, the making of a documentary to mark the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Britain was an intensely personal journey. I was born in February 1940 so I was just six months old as the battle raged overhead.

Our soaring and twirling Spitfire was painting the sky with a hula hoop of happiness...

I grew up in London, a city devastated by the bombing. I am, you might say, a Blitz Baby.

I was too small to remember much about it but all of us alive at that time were shaped by the events of the war. My parents, Arthur and Olwen, were honest, working-class people who raised my brother Arthur, sister June and me with the values of that era – patriotism, stoicism, honesty, concern for your neighbours and judging a man by what he did rather than what he had.

My mum worked as a char when I was growing up and my dad was a fishmonger, but during the war years he had another role, too. He was in the Reserves, a kind of Home Guard.

The stories my father used to tell about his service in that organisation had echoes of Dad’s Army about it. We lived in Finchley, North London, and so he and his compatriots in the local division would plonk themselves on top of the nearby Southgate Gasometer with an ack-ack gun and fire at German bombers as they flew overhead.

The problem was that they never actually had any real bullets because they were all being used in the war effort elsewhere. My dad would come home and say: ‘We could have hit them if we had ammunition!’ It wasn’t funny at the time, although he laughed about it years later when he retold the stories.

Thinking back, he was lucky to survive. Can you imagine if a bomb had hit the gasometer? He would still be flying now. When you look at the large casualty figures – four million British homes destroyed and more than 60,000 British civilians killed in bombing raids during the Second World War, two-thirds of those during the Blitz – we were lucky to survive at all. At home we had an air-raid shelter and we were religious about observing the lights-out rule.

One little chink of light could guide a German bomber in, and that would be it. Even now, the rule is so conditioned in my brain that I’ll never leave a light on in the house unnecessarily and I can get quite grumpy when other people do. Yet still, even with these precautions, everyone in London was vulnerable. One night, a German plane scattered bombs all around us: one landed just up the road on the Gaumont cinema, another in Percy Road, the street next to us, and a third in our road, Lodge Lane.

If the bomb had dropped just 150 yards to the right, I wouldn’t be here today. Years after the war had ended, the scarred landscape of London remained the backdrop of my childhood.

Our gang played on the bombsite that had been left in Lodge Lane, while a rival group played on theirs in Percy Road. When it got close to November 5, we would creep over to the rival bombsite to sabotage the bonfire they had been building. We would try to set fire to theirs, they would try to set fire to ours.

As young lads, around the age of ten, it never occurred to us that these ‘playgrounds’ were created by a bomb and that people must have died there. But now aged 70, I find myself reflecting on the human cost in both civilian and military terms.

We need to remember, for example, that during the war more than 55,000 men in Bomber Command never made it back – 5,000 of those were from Elvington, near York, one of several airfields I visited while making my documentary. Indeed, the life expectancy of a fighter pilot at the height of the battle could be counted in days. And I’ve been thinking not just about the pilots – perhaps the bravest men in the world – but of all the men and women on the ground who helped us defeat the forces of Nazi Germany.

These include the crews who looked after the planes and kept them ready constantly for service. I met Joe Roddis, who had been an 18-year-old flight mechanic in 1940 at RAF Coningsby in Lincolnshire, now home to the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight.

‘Without us, it was no good,’ he said simply. ‘And without them, the pilots, it was even less good.’

Then there was the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, affectionately known as the WAAFs. By 1943, the WAAF’s numbers exceeded 180,000, with more than 2,000 women enlisting every week.

During those dreadful months of the Battle of Britain, from July to October 1940, it was WAAFs such as the redoubtable Hazel Gregory, then aged 19, who worked as ‘plotters’ in radar stations up and down the country. It was their job to map the progress of Luftwaffe planes as they flew towards Britain.

During our interview, I looked into Hazel’s eyes as we sat together 60ft below ground in a bunker in Uxbridge that had been the Fighter Command centre for London and the South East.

‘Did you ever worry that the Germans would succeed?’ I asked her. ‘No,’ she said. ‘There was tremendous spirit and nobody thought for a single moment that we wouldn’t win.’ What better example of the Blitz spirit could you ever encounter?

And let’s not forget the Royal Observer Corps, a band of unarmed civilians stationed at hundreds of observation posts all over the country. While filming, I went to the wartime location of one such post, codenamed Sugar Three. There I met Dennis Bates and John Elgar Winney, two of the 30,000-strong army of volunteers who had spied on the skies through binoculars. ‘What we could do that the radar couldn’t was to tell what type of aircraft were coming, how many there were and what direction they were flying in,’ Dennis told me. They would call this intelligence through on a crackling GPO line to their own HQ, which then alerted Fighter Command, which would scramble Spitfires and Hurricanes.

‘The Observer Corps were vital in the Battle of Britain,’ John added. ‘Without us it could not have been won.’ The most important lesson, then, to emerge from the making of the documentary was that we owe a huge debt of gratitude to so many people. As Terry Kane, another of the veteran fighter pilots I was privileged enough to meet, explained: ‘It wasn’t just the pilots who won the Battle of Britain. In many senses, it was the whole country.’

If Britain had not come together at that time, as it did, to defeat theNazis, none of us would have lived the kind of life that we have been able to live, or had the kind of freedoms I know that I have certainly enjoyed.

So the documentary became not just about those brave fighter pilots immortalised in Winston Churchill’s post-Battle of Britain victory speech in which he said: ‘Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.’

It was also a tribute to the ‘many’ behind the ‘few’: the unsung heroes of the Battle of Britain. Most importantly, I wanted to reveal the human face behind the history lesson, although, of course, the history itself is important.

War had been declared in 1939 and by the end of June 1940 the German jackboot went right through most of Europe, including France and Poland, and it was also well on its way to Russia. Britain was next on Hitler’s hit-list and by August 1940, German invasion barges were assembling on the French coast.

However, they could not set sail until the Luftwaffe had wiped out the RAF, both in the air and on the ground. We didn't feel brave, we just got on with it

It was essential that the RAF prevailed because it was the only thing standing between freedom and the Nazis, and if it had capitulated we would have been annihilated.

Yet we were horrendously outnumbered – 4,000 German bombers and fighters massed against just 600 RAF fighters.

‘But the question of being outnumbered didn’t come into it because you were always outnumbered,’ said Paul Farnes, who was a 21-year-old Hurricane pilot in 501 Squadron at the time. ‘But we had one big advantage: we were fighting over our own country and so we knew all too well what we were fighting for.’

Unwisely, Hitler had not reckoned on the indomitability of the British spirit and the men and women of the RAF. His generals had told him it would be easy, but even after attempting to destroy our airfields before turning his attention to cities such as London, Aberdeen, Bristol, Coventry and Hull, still we would not yield.

Hitler was left scratching his head over his force’s inability to defeat us. In the end, I suppose he said: ‘OK, we’ll come back to that later’ which was a big mistake because he never got to do that. The Battle of Britain was not just a defining moment in our nation’s history, it was also the absolute turning point in a war that ultimately saw the Nazis defeated.

But I also wanted to take a closer look at the men and the machines – the pilots and the planes – that gave the Luftwaffe such a run for their money in 1940. I’ve always had such tremendous respect for the men who fought in the Battle of Britain and I am a patron of the RAF Benevolent Fund.

I also have a pilot’s licence myself, although in my case, until I flew the Spitfire, I had only ever flown helicopters. I got my licence in 2005 after my wife Gill bought me a flying lesson as a birthday present.

I found myself so completely hooked on flying that I was determined to get the necessary qualifications. A couple of years ago, I bought my own helicopter, a Robinson R44. I use it occasion-ally to fly myself to sets where I am filming or to business meetings.

From Buckinghamshire, where I live, I’ll fly for an hour to Norwich, perhaps, or to the south coast. But I never fly more than that. It’s more than enough in terms of the mental workload because it takes a lot of concentration. So I’m lost in admiration at the way our pilots were able to fly up to six sorties a day. And they did it without any of the mod-cons that pilots have today. They would have been alone and freezing cold, heading towards an enemy that had only one objective in mind. It was a shoot-or-be-shot situation. It would have taken nerves of steel. During my visit to RAF Coningsby, I was shown the oldest airworthy Spit-fire in the world. It is the only one still flying today that fought in the Battle of Britain. A team of proud fitters showed me the workings of this magnificent plane, including its eight guns.

Each was loaded with 350 bullets, which seems impressive but this gave the pilots only 12 to 14 seconds of fire-power, after which they had to come back to base to reload before going out again.

‘Ninety-seven per cent of the bullets missed. We were very bad shots,’ Tom Riley, another of the veteran fighter pilots, recalled with a smile. ‘But the only thing to do was to get as close as you could to the bloke in front. If you could almost touch him you could probably hit him.’

Like so many of the pilots, Tom had been heartbreak-ingly young at the time that he risked all for his country. He was just 19 when he flew his first Battle of Britain mission. The average age of fighter pilots was 22.

Amazingly, the pilot in command of one of the squadrons that bombed Dresden later in the war was only 24.It’s difficult to imagine young men in their early 20s these days being able to stand so much responsibility.

But, perhaps, if the enemy was at our door, as it was then, they would find the courage.Back in 1939 these young men had joined the RAF as volunteers and learned to fly in Tiger Moths, but with the outbreak of war they were called upon to defend our skies in Spitfires and Hurricanes against the Messerschmitts and Dorniers.

It was not what they had signed up for and so, in that sense, their lives were not given for this country but taken by it, because no fool ever actively wants to go to war.And yet they discovered such tremendous heroism and tenacity within themselves, although they would never dream of boasting about their own achievements.

‘I don’t think anybody felt particularly brave,’ former Hurricane pilot Paul Farnes said. ‘It was what we had been trained for. It was our job and we just got on and did it.’During my interviews, I wanted to find out what – aside from luck – separated those who survived from those who died.

According to Bill Green, a fighter pilot with 501 Squadron who flew 29 missions himself before being gunned down and baling out, it was the exhausted and the inexperienced pilots who were first to be shot down.

‘Most of the casualties were inexperienced pilots joining the squadron one day and being shot down the next,’ he told me. ‘The ones who stayed alive usually had a great deal of experience.’

Paul Farnes added: ‘The really good pilots all had a sixth sense. They didn’t need to look round to see where the danger was – they felt it instinctively and dodged the bullets.

‘Those who had intuition survived and those who didn’t got shot down, I’m afraid. It was brutal.’

At RAF Hawkinge, now the Kent Battle of Britain Museum, I saw just how brutal things were for myself. The museum still holds the remains of 650 crashed aircraft – a propeller from a German Dornier 17 is riddled with bullets, showing just how many shots it must have taken to bring down such an aircraft. But while our planes did fall, the British spirit never faltered, and in its own way, life went on. People still fell in love, babies were still born, and the young still tried to enjoy themselves.

For example, after working at Fighter Command at Uxbridge, Hazel Gregory would travel into London to go dancing. Was she worried about the bombers, I wondered. ‘No,’ she replied. ‘We were young and we wanted to have fun.’So in the midst of it all she wanted what probably every ordinary young woman wanted at the time: to meet a good-looking pilot or soldier and have an innocent dance.

They all wanted to forget about the worries of the war for an evening and just have a good time. Again, I felt totally moved by what she told me.There is an emotional thread that runs through the documentary – the same emotional thread that still binds us and tugs at us 70 years after the events of that fateful period.

We are still fascinated by that time – by the Second World War in general and the Battle of Britain in particular – because it was our finest hour. And it was the spirit of the men and women just like Hazel and all the fighter pilots and those who ensured that they could keep on flying that made it so.

Flying high above the White Cliffs of Dover at the end of the documentary, the soaring, twirling Spitfire painting the sky with a hula hoop of happiness seemed to embody the very spirit of those brave men and women and of the Battle of Britain itself.

After the barrel-roll of victory, I retook the controls and we headed homewards.‘You certainly know how to affect a man’s heart!’ I told Carolyn.

And, oh, how she did.

David Jason: Battle Of Britain will be shown on ITV1 on September 12 at 7pm. Albert’s Memorial, a drama about Second World War veterans in which David Jason stars, will be shown on the same evening at 9pm.

Monday, July 12, 2010

Veterans gather on clifftop to celebrate 70th anniversary of Battle of Britain

A Hurricane was unable to fly due to technical problems. The event was attended by Prince Michael of Kent, who took the salute, along with the RAF's most senior figure, Air Chief Marshal Sir Stephen Dalton. 'There's been a complete mixture of people here, young and old, lots of families, aircraft enthusiasts,' spokesman Malcolm Triggs said of the annual event was the biggest memorial day yet.

'It's particularly important for youngsters to understand the history and to see the veterans here and be able to get an idea of the bravery they showed. 'This anniversary is a very significant event,' he added. He said 19 veterans were in attendance, with some of them taking part in the parade. During the summer of 1940, nearly 3,000 British and Allied airmen took on the Luftwaffe and ended up preventing a German invasion of England.

Then prime minister Winston Churchill famously said of their actions: 'Never was so much owed by so many to so few.' Officially the conflict took part between July 10, 1940 and 31 October that year, when the Luftwaffe called off bombing raids due to mounting losses and bad weather. A total of 544 British and Allied airmen lost their lives during the period. It is thought that only about 100 of the veterans who took part in the battle survive. "LEST WE NEVER FORGET"

Sunday, June 20, 2010

A call to reason for the Gulf of Mexico oil disaster

I wanted to post on my blog a call to reason! Something to the South of us in The United States is troubling me very much! It is the Oil spill disaster in the Gulf of Mexico. Our Father's and Grandfather's have won many wars againts tyrants such as Hitler, Mussolini and people who wanted to rule the world without a democracy!! I think that this oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico is like a war and we are not winning it right now! This spill is gushing millions of gallons of oil, methane and a lot of garbage that is killing wildlife and marshes and destroying the lives of thousands of fishermen, people related to the tourist industry in the United States and many more other working class people. This is all very sad!

BP and the American Government must do everything in their power to stop this oil spill before it gains the Gulf Stream and heads out to the Atlantic Ocean. This oil spill has already done enough damage and is now affecting the livelihood of people in Louisisana, Alabama, Florida and will eventually stream North with the Oceans current! I don't even want to think if there is a major hurricane in the Gulf although scientists and the people of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) predict that this hurricane season could be one of the worst on records due to the Gulf water and the Atlantic ocean being warmer than normal due to the oil absorbing the heat of the sun rays in the ocean.

I always like to talk of our veterans and all of their great accomplisments and history but this is oil spill is too important not to mention to the world through my blog and the way i feel about this disaster! This oil spill will go down in history as being humanities worst man made disaster!

Please, help in any way you can!! Please donate to an accredited Wildlife funds, I have posted on my blog a logo of the National Wildlife Federation on the top left side, all you need to do is click on the logo to be re-directed to the National Wildlife federation to help maintain the eco system of the Gulf of Mexico and the wildlife. There are other sites where you can donate to help the people of The Gulf, write to your member of Parliament if you are in Canada or the United Kingdom, write to your senetor if you live in America and tell them that this spill must be stopped urgently because it is killing the Wildlife in the Gulf and destroying the Eco system of the Gulf of Mexico and destroying the people's lives.

You can contribute to Gulf Aid Acadiana. Gulf Aid Acadiana was founded by three friends with the help and support of many other friends. Singer-songwriter Zachary Richard is recognized for his committment to environmental and cultural causes. Author of 18 albums in both French and English, as well as several collections of poetry, he is best known for his efforts to promote the French language and Cajun culture of Louisiana. Their link is

http://gulfaidacadiana.org/

I wish i could help in the Gulf as a volunteer but being here in Canada is impossible for me! At least, if i can do anything through my blog, it will already be a step for me in the right direction. Our veterans have helped win World Wars and bring peace againts tyranny and madmen but this is another kind of war that we all must participate in so we can win it! For the people of the Gulf, for the wildlife and this beautiful planet EARTH that we all live on!

God bless you all and let's win this war in the Gulf like our veterans did! It is urgent and the Gulf of Mexico is being polluted by the minute and will take generations as of today to bring it back to it's original state so every hour and every minute counts! This is very urgent!

Thank you for your help and your call to reason in this sad situation in the Gulf of Mexico. Let's win this war once and for all and let's do it fast!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)